Henrietta Lacks succumbed to cervical cancer at 31, yet her cells persist. The tragic tale of this young African-American mother of five reshaped modern scientific research, with Henrietta’s rapidly proliferating tumor cells influencing over 70,000 medical studies.

To observe and treat diseases, scientists rely on immortal cell lines cultivated in laboratories. Dr. George Gey of Johns Hopkins Hospital discovered the first immortal cell line in 1951, derived from a cancer-stricken woman, Henrietta Lacks. Unaware of the impact, Henrietta passed away shortly after. The family only learned about HeLa cells, named after Henrietta Lacks, 25 years later.

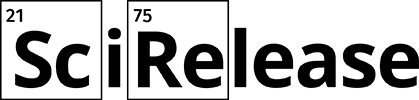

Normal cell cultures have a limited lifespan, typically 15 generations. HeLa cells, however, regenerate approximately every 48 hours, proliferating endlessly. Johns Hopkins Medical Center deems HeLa cells one of the most significant scientific discoveries of the last century.

HeLa cells contributed significantly to combating Parkinson’s disease, tumors, leukemia, hemophilia, HIV, herpes, Zika, measles, mumps, and played a pivotal role in developing the polio vaccine. Testing on HeLa cells proved more cost-effective than monkey cells. The papillomavirus vaccine, stemming from research on Lacks’ cancer, reduced infections among young girls by two-thirds.

Rebecca Skloot’s bestseller, “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” adapted to screen in April 2017, showcases society’s fascination with the immortal woman. Henrietta Lacks achieved eternal life through millions of saved lives and her immortal cells.